Fish Camp

The family cabin affectionately known as the Loon's Roost has seen a lot—especially on one particular weekend each year.

Jake and I were sawing away at a fallen tree with a two-man buck when a Chevy Tahoe turned off the gravel road into the driveway.

My dad was in the driver’s seat and his friend Joel was riding shotgun. We watched them pull in.

I took a long pull from a can of Hamm’s and wiped my mouth with the back of my hand. Jake leaned back, mopped his brow.

“About time you guys showed up,” he said.

We bent back down and made a show of continuing our manly work.

“You guys are full of it,” Joel hollered.

He was hanging halfway out the window. No sense waiting five seconds for my dad to park when he could start talking right away.

Jake and I broke into laughter. I greeted Joel with a hug.

Dahlke piled out of the back seat. He’d caught a ride from Farmington with my dad and Joel.

My dad took in the scenery.

“Looks like fishing will have to wait,” he said.

A bad storm had rolled in the night before. There were a few trees down in the yard. A mature pine had snapped off and was lying on the roof of the fishing shed.

Fortunately for me and my dad, it was the annual guys’ weekend fishing trip at the Akin family cabin. There would be plenty of hands to help. And the witty banter, insufferable in any other setting, would help make for light work.

Joel was already providing a steady stream of commentary on everything from professional golf to how to approach the yard clean-up.

“You need a beer?” Dahlke asked.

“Only if you’ve got a cold Douly,” Joel replied. He was the only guy I knew who drank O’Douls on the regular. I didn’t understand it at the time.

The other guys arrived somewhere in the scrum of unpacking and getting ready to take on the downed trees.

I returned the antique saw to its spot on the garage wall. Uncle Haltey wandered around picking up sticks and singing the Lumberjack Song from Monty Python. Dahlke fired up a chainsaw and started clearing limbs from the first downed tree.

It’s always good to have an Eagle Scout around.

The origins of the annual men’s weekend retreat to the Loon’s Roost are unclear to me. Maybe it started in the early 80s, soon after my grandpa bought the property. Apparently in those days you could afford a cabin on the water on one public servant’s salary. Back then, my dad’s softball team stayed at the cabin while playing in a nearby tournament. A more recent iteration was his yearly golf and fishing trip in the late 90s and early 00s. The traveling trophy from that era consisted of a bottle of Advil with a golf ball hot-glued to the lid and two jigheads serving as handles. It sits in a place of honor on a shelf in the corner of the kitchen.

Today, my dad simply refers to the annual gathering as “Fish Camp.” For all of us, I think, there’s a lot more to it than that.

When the storm had rolled through in 2012, there were nine of us that made the trip. If the group was a recipe it would be a hotdish, extra salt.

Joel - Several years younger than my dad, they first met when Joel was a hotshot junior high pitcher throwing illegal curveballs on a baseball team coached by Uncle Haltey. He worked at the hardware store in Farmington, then for the local electric co-op.

Uncle Haltey - No relation to me. One of my dad’s lifelong best friends. Recovering liberal arts major and general philosopher-grump.

Fumblitis - Uncle Haltey’s teenaged son. Tagged with the moniker by Joel after repeatedly dropping fishing equipment in the boat.

The Provider - One of my dad’s best friends. The self-proclaimed “Provider” because he cleaned all the fish—and says he caught them all, too. Good listener, bad jokes, sound advice.

Mr. W. - An independent older man from Farmington with a developmental disability. He supported and was supported by many in the community over the years, including my grandparents. Before my time, he used to have an old black cat that he walked around town on a leash. Mr. W. loved to fish.

Dahlke - Jake Dahlke, my high school buddy, karaoke partner, and best friend. Up for anything, jack of all trades, foxhole-caliber guy.

Jake - My college and 20-something roommate, best man, and best friend. Typically a positive, moderating influence for everyone. Generally quiet, occasional top-10 zingers.

My dad - The patriarch of the trip. Second-generation Loon’s Rooster. Central connection point. Likes fishing almost as much as Mr. W. Competitive.

And yours truly - Jacob—”Jake” to family, “JJ” to everyone else—Akin. Lots of Jacobs born in the 80s. Two of them happened to be my best friends.

After clearing up the worst of the timber, it was time to hit the water. My dad took Mr. W., Uncle Haltey, and Fumblitis out in the pontoon. The Provider invited Joel to hop in his boat. That left the Jakes.

We piled into my late grandpa’s seasoned Alumacraft with our fishing gear and a cooler of beer. The 9.9-horse motor labored under the weight of an all-conference wrestler and two college football players, still big but already starting to soften up.

We told some tall tales and caught a few fish. The Jakes talked a good game, but we didn’t know anything about life. How could we? We were 23.

By supper time on Saturday, we’d caught enough keepers to have a fish fry. Fumblitis hauled up the bucket of fish from the dock as The Provider honed his filet knife. Jake set up the outdoor kitchen. Joel and Dahlke teamed up to batter and cook the fish as my dad looked on and offered some pointers. Were they helpful suggestions? I guess that’s in the eye of the beholder.

There were a few minor flare-ups but a well-timed joke or two ensured that nothing boiled over. The end result was a perfect meal of walleye, perch, and crappie accompanied by baked beans and fried potato slices, all of it washed down with Hamm’s and Captain Morgan, brandy on the rocks, O’Douls, Mountain Dew, milk, Monster Energy, and root beer, depending who you asked.

After dinner, I sat on the deck with Jake and smoked a cigar. I kept an occasional eye on the life-jacketed Mr. W., who was bobber fishing for bluegills from a lawn chair on the dock.

Earlier, he’d tried to pull a fast one. Apparently the rest of us had taken too long to get moving again after lunch. When the fish called, Mr. W. could be counted on to answer.

“What’re you doing down there without a life jacket?” Joel shouted through the window screen while washing dishes.

Mr. W. gave a dismissive hand flap over his shoulder. “I’m fishing!”

“You can’t fish without a life jacket!” Joel fired back down the hill.

Mr. W. waved him off again and plunked his worm in the water.

“Why I oughta come down there and kick your ass!” Joel yelled.

Intervention seemed like the prudent path. I went down the steps to the dock and gave Mr. W. his life jacket. He put it on without debate.

“Thank you, Jacob,” Mr. W. said. He’d known me since I was a small child. “Jacob, you tell that Joel to watch out. I’ve got an Irish temper.”

“I’ll let him know,” I replied.

Joel helped Mr. W. dish up for supper and sat next to him at the kitchen table for the evening meal. They went on like old friends. Having spent most of their lives in Farmington despite being born a quarter century apart, I guess they kind of were.

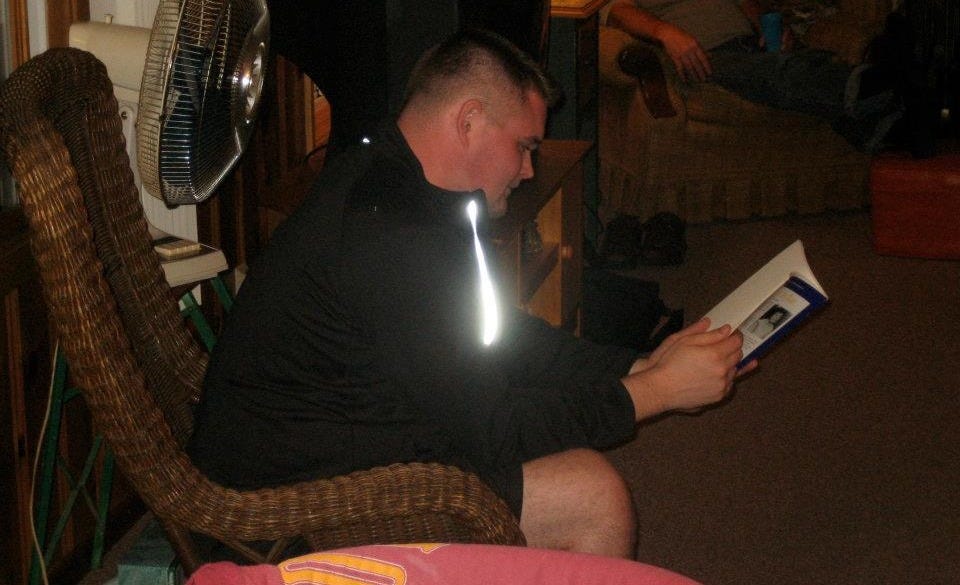

Later that night, after Mr. W. had gone to bed, the rest of us were sitting around in the living room. The play-by-play of a Twins game provided background noise from the television at the edge of the room. I was paging through an old book of poetry I’d pulled from a shelf, two and a half sheets to the wind, when someone suggested I read a poem aloud.

I don’t know if they forgot that I was an English major.

I read a poem.

“Your turn, lips,” I said to Joel.

He somehow managed to yap constantly without ever being truly annoying. He shrugged and gestured for me to toss him the book. Joel thumbed through the thin volume for a minute, then loudly cleared his throat and read a poem.

Everyone snapped politely.

Dahlke asked for the book. He read a poem.

My dad read a poem.

Fumblitis declined.

The Provider read a poem.

Uncle Haltey wouldn’t read one, at least that first year.

Jake read a poem.

I read another.

Joel died of pancreatic cancer in 2016 at the age of 52. The year before, he’d won the Minnesota state powerlifting championship in his division.

A few months before the end, my dad called and said that he and Joel were making a last-minute trip to the cabin. It was mid-September and the forecast called for a beautiful early fall weekend. Dad wanted to know if I could make it. I'd just started in a new position at Gustavus and I didn't know if I could get away, but when things looked clear at five o’clock on Friday, I hustled home, grabbed a bag, and hit the road.

After catching up with mostly-true stories that night, we loaded up the pontoon after breakfast on Saturday. None of us really expected to catch any fish that time of year, but the sun was shining enough to take the chill out of the air. We trolled back and forth for awhile, maybe pulling in a fish or two, before Joel tied into a big one.

Of course, because it was Joel and he liked to talk, we didn't believe him at first.

But it was even more remarkable because we all knew—even though nobody said it—that this was Joel's last trip to the Loon's Roost. And on that bright, chilly fall day, when the fishing wasn't any good at all, somehow this big northern found Joel's hook. And somehow the six-pound line, brittle and worn from a summer of wind and water and sun, cut and re-tied a dozen times over, didn't break. When we got the big fish in the net and brought it over the railing into the boat, the lure, which had been hanging loosely from the side of the fish's mouth, immediately fell to the floor of the boat. But there was Joel smiling, holding his northern for one last Loon’s Roost photo before releasing the fish to fight another day.

"It was the biggest one I've ever caught," he said later that night. There was no bravado in his voice, honest this time despite all the fish stories he’d told over the years.

I remember that trip all the time.

The Sunday morning goodbyes at Fish Camp are quick. Nobody wants to linger too long or say too much. Sometimes, a guy packs up and sneaks off before everyone is awake. You can’t catch the magic every year, and even when you do it always wears off quickly.

I get it. The morning sun’s not the same when you need to head back to the real world.

But we’ve done the poetry reading every June since that first time back in 2012. Guys have even penned a few of their own.

I’ll leave you with one today.1

Fish Camp by JJ Akin May 2024 Two generations and the spectre of another, and a few other ghosts besides, depending how you define the term— they haunt a cabin called the Loon’s Roost each June. The scene is not of eldritch horror, or supernatural auroras winding through Norway pines and tickling the back of their necks. A charge in the air all the same, a certain energy, positive mostly, excitement even, or what passes for it in a man today, expectations all year of stories to be told. A worship service, a revival meeting of water, sun, fishing, fire, laughter, food. And on Saturday, after the last fingers of daylight reach for the sky, and finally lose their grip on the horizon, the men pause the Euchre game, and read poetry aloud. Two old drinkers, three decades sober off the brown stuff, red-eyed tonight but that doesn’t count, anyway, at least two more who aren’t done yet, and it’s they who raise a toast, and recite their poems the loudest, walking into middle age with the confidence of relative youth and maybe a little faith remaining, or the belief, at least, that there’s still time to repent. A few other characters around the room, young, old, layered, undiagnosed, each unexplainable to the uninitiated. With advanced degrees and with applied experience in the hard lessons and ways of the world, setting aside the politics of the moment, the men take up well-thumbed chapbooks, swap garage-sale anthologies, unfold their own scribbled, earnest words, written haltingly with an unexamined mix of embarrassment and pride over the course of the last year. There is no conductor as the gravelly choir sings vespers. Each soloist hits his own discordant notes of tempo, meter, intensity, and rhyme. But a relentless crescendo swells through the room as the sections come together— Is this what God is? A summer watchnight symphony of men together, for a short time, unafraid? And it’s standing room only for the visiting spirits who gather, those who have wandered in across the years— some longer than others, some pulled by life in other directions, some no longer welcome, some gone for good. “But why should I lie here longer? I am not dead yet, though in years, And the world’s way is yet long to go, And I love the world even in my anger, And love is a hard thing to outgrow.” “American Portrait,” is the benediction, whispered almost, as the songbook closes for another year. Tomorrow is Sunday, but these men took communion early, the only kind that seems to work. Afterward, the glare of reality returning, both clock hands nearly vertical, fading, I look at these people I love each picking up again the things they carry, whether they know it or not. It’s a wistful recognition when, quietly drinking in the scene, a question comes to mind— I smile to myself, leave it unspoken.

The italicized text is my favorite except from one of my favorite poems. It’s called "American Portrait: Old Style” by Robert Penn Warren.

🫰🫰🫰🫰🫰🫰🫰🫰🫰🫰