Lutefisk, Lefse, Copenhagen Snuff

A tight squeeze into the moldy swimsuit of memory.

I have the dimensions of a fire hydrant.

Five-nine but I like to round up. About 225 pounds if I’ve been watching my diet and exercise. The old football muscles in the chest and shoulders migrated south several years ago. I wear wide sunglasses and all of my shirt sleeves are too long because I need to size-up to get a neck measurement that fits.

Since we’re talking about my body, now seems as good a time as any to tell you that my pancreas doesn’t work. Don’t worry about that for now, it didn’t happen until well after my days of athletic glory as a Farmington Tiger.

Where was I?

Oh yeah, fireplugs.

A lot of people look at me and think I used to be a wrestler. I get it. And I was a fullback on the football team, so that makes sense. But back in those schoolboy days, once autumn wore on and the weather turned cold, I didn’t wrestle or play hockey or shoot hoops. I was on the swimming team.

Our co-coaches were both middle school physical education teachers. The older guy was a relentless recruiter and more than a little eccentric. The bad cop of the coaching duo was a woman in her mid-20s who’d played high-level college softball.

I like to think they asked me to join because my athletic talents in gym class were so obvious that they had to have me on the team. The reality is that they tried to talk everyone with a pulse into joining. Swimming was a relatively new high school sport in Farmington. The program was still trying to break into the mainstream. And you can fit a lot of guys in eight lanes.

My friend finally talked me into it in eighth grade. We played on the same baseball team. He said I was an excellent swimmer. Like a fool, I believed him. Really, he wanted me to help absorb some harassment from his older brother and friends, who were also on the team.

I was confident in the water. I passed all my lessons and spent quite a bit of time at the local municipal pool and in the lake up north, but swimming laps was new. And, to be honest, I never grew to like that part of it.

Practices were grueling. Minnesota has long, dark, subzero winters. We practiced every day after school except for meet days. We were on the deck by 5:30 a.m. for early practice a few times a week. To paraphrase one of my old teammates, who said it best:

You get out of your warm bed and freeze in your cold room.

You get dressed, go outside, and shiver in the early-morning air.

You warm up in the car, then you freeze on the way into the building.

You walk through the warm pool, then shiver while pulling on your suit in the locker room.

You stand on the deck looking at that still, chemical-blue water, and you know exactly how cold and unpleasant it will be.Then you dive in anyway.

Some days, I never went outside when it was light. You’d get to the pool before sunrise, go to school, then to practice, then leave when it was dark and cold.

We’d pull, kick, and swim miles and miles to prepare for races that were only 50 or 100 yards. (Yes, there are many race distances longer than that. But not for me. Fireplug, remember?)

As younger guys on the team, my classmates and I endured the frequent lash of wet shammies cracked with pinpoint accuracy by the older divers. One of the senior swimmers liked to sneak out of the pool when the coaches weren’t looking, climb the diving board, and cannonball on top of you in the middle of a set. One second you’d be swimming along, the next you’d be six feet underwater, gasping for air and hoping your back wasn’t broken. I thought it was just part of being on the team.

And there were more chronic discomforts.

Your muscles are always sore. Your skin is constantly itchy from the combination of chlorine, frequent showers, and winter air. If you don’t take your time with your suit after practice or have a bunch of extras on hand, you’ll always be pulling on a pair of jammers or a Speedo that isn’t quite dry.

After a while, you develop a complicated love-hate relationship with your teammates and the pool. You evolve a strange sense for analyzing the water without ever thinking about it—some pools feel fast, some feel slow, and some even feel “dry.” I can’t explain it, but swimmers will understand.

Frankly, a lot of it just wasn’t much fun.

But racing?

The anticipation of the starting buzzer. Launching yourself from the block and cutting perfectly into that blue mirror. Pulling like crazy for the wall. Breaking the water at the turn and seeing just a flash of your teammates as they lean over and scream at you from the deck. Clutching at those muffled cheers to find a new gear, then peeking over to the next lane and accelerating even more.

The racing was pretty fun.

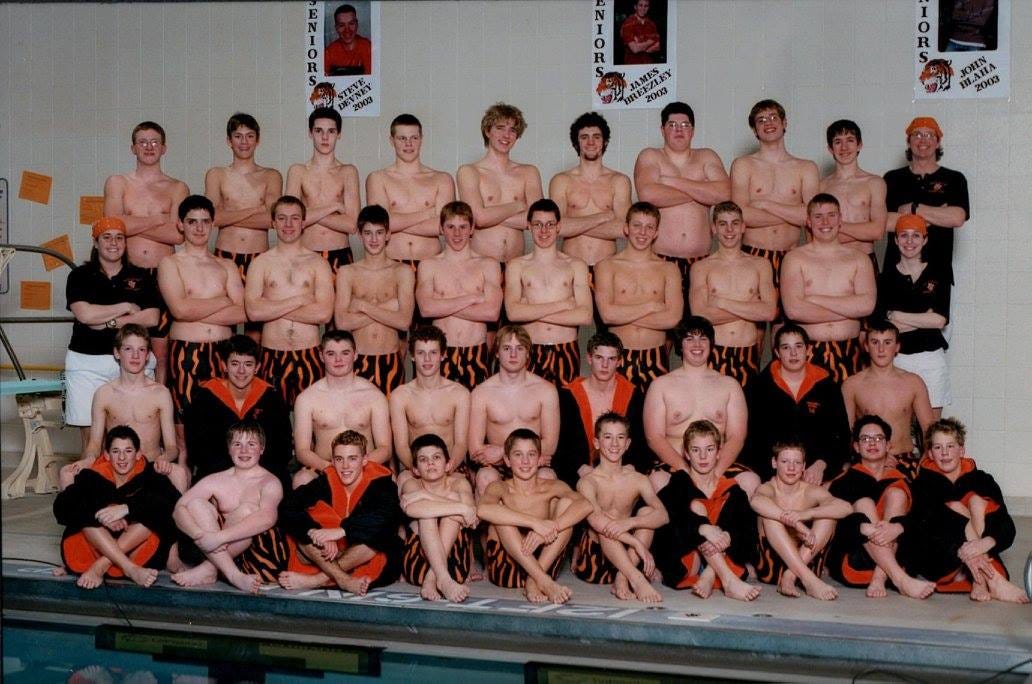

And the camaraderie. A bunch of kids from all kinds of different backgrounds and abilities and social groups, brown-nosers and burn-outs, recruited by a wild-eyed middle-aged diving coach and a tough-but-loving 25-year old who felt ancient to us. God, were we young.

Before every meet, the team would gather on the deck. Guys wore tiger-striped racing jammers and long, fleece-lined coats. We’d throw our arms around each other, form a circle, and lean in. One of the captains or coaches would count us down.

“Lutefisk, lefse, Copenhagen snuff!” we screamed. “Farmington Tigers, ruff, ruff, ruff!”

It was an old swim cheer that one of our coaches had learned back in high school. God knows why we used it. It all seemed normal to us at the time. Totally normal to scream a nonsensical chant that has nothing to do with your school mascot to get hyped up before a meet. Totally normal to engage in horseplay that bordered on assault. Totally normal to have a woman coach who you obeyed without question. Mostly good lessons, a few that could’ve perhaps been learned in a less experiential manner. Oh well.

My sophomore year, I was doing pretty well in the 100-yard butterfly. The fly is a beautiful stroke when you watch it on television every four years, but as high school swimmers we were not its most efficient technicians. Still, even the best in the world can’t mask how exhausting it is. From the second you enter the water, you’re holding a tight streamline and propelling yourself forward with full-body dolphin kicks. As you come to the surface, you rear up and throw both arms out wide and fling them forward in front of you as you try to steal a gasp of air. Two kicks per stroke, and if you don’t time them right you won’t get your shoulders high enough to take the next one. As your arms enter the water you’re already pulling, preparing to lurch forth again. You can be two feet ahead of the next fastest swimmer and lose because you misjudged your final stroke into the touchpad. The butterfly is unforgiving.

In one race towards the end of the season, I ended up in the lane next to a conference rival. We’d been back and forth all year. On the final stroke, I thought I had him. We touched the wall, broke the water, and snapped our heads toward the scoreboard. He beat me by a split second.

I looked at my dad up in the stands and put my thumb and forefinger an inch a part.

“I was this close.” He couldn’t hear me across the pool and the screams of the crowd, but he knew exactly what I said.

When I got home that night, there was a piece of paper lying on my pillow. It was a printed picture of a University of Minnesota swimmer talking with his coach after a race. He was using same hand gesture I’d flashed across the pool that afternoon.

Below the picture, in black marker, my dad’s distinctive block print.

“It’s all the little things that make a big difference.”

A few weeks later, I broke the school record in the 100-yard butterfly.1

When I think back to those days on the swim team, the lessons are clear. I learned the value of:

…showing up every day.

…working with a wide array of people, some you love and some you can’t stand, and finding a way to do it because that’s what the team needs.

…managing the aches and emotions of a long season.

…paying attention to the little things.

I retired from swimming after that sophomore year and spent the next two winters lifting weights for football and baseball. I still lifeguarded and taught swimming lessons. My coaches and teammates didn’t understand. My parents, thank God, didn’t push me too hard to keep going.

I was proud of what I’d accomplished in the pool, I just wasn’t sure if I had the energy to do it all again. Of course, I couldn’t articulate that at the time.

Looking back now, would I do it differently? I don’t know.

I liked winning more than I liked the activity itself.

It’s a recipe for success, but not the sustainable kind.

The record’s been broken countless times since. We cling to glory, however minor, however fleeting.

Nice work, JJ! I really like the title and how / when its meaning is revealed. It is attention grabbing but does not distract from the narrative leading up to its reveal.